“So what the hell do we do now?” I bark at my partner through the wind. I’m at an edge — mentally and physically — standing above a cliff on Rainier’s Ptarmigan Ridge.

Confidence crumbles beneath my ski boots and into the cauldron of clouds, boiling with uncertainty. As if to give us the finger, out of the storm pokes The Needle, a landmark spire jutting off the Mowich glacier.

Then the answer I’d rudely requested a moment before. “We wait,” says Chris Minson, my friend and climbing partner on this crazy trip.

A mountain of superlatives and surprises, Rainier has drawn upon most of our skills. It only makes sense we practice the hardest of all now three days into the trip: Patience.

About The Route:

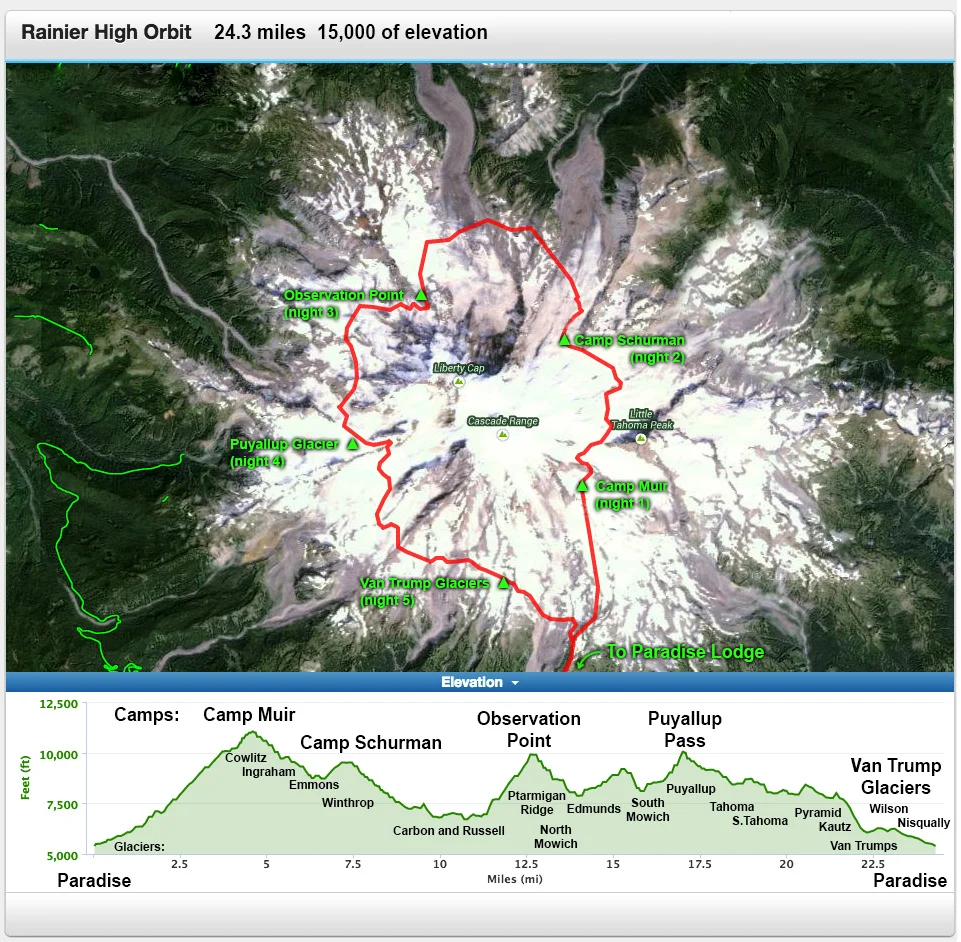

“High Orbit” is a rarely climbed/traversed route on Mount Rainier. It takes a 360-degree line around the massive volcano, yo-yoing between 7,000 and 10,000 feet via climbing routes and glacier traverses. It’s a 20+ mile trip, and for much of it climbers are on skis and roped, often with an ice axe in hand. Along its course the High Orbit tags pieces of the routes that helped define American alpinism: Liberty Ridge, Curtis Ridge, Ptarmigan Ridge, Edmunds Headwall, Willis Wall, and more.

Details —

- The route in miles: 24

- Name: High Orbit

- Glaciers Crossed: 17

- Time: 6 days (actual), (two 1/2 days)

- Pack weight: Base, 40#; 50# with water

- Elevation Gain/Lost: 15,000 feet

Itinerary —

- Wednesday. Skied for three hours from the Paradise lot to Camp Muir

- Thursday. Side-stepped for nine hours down Emmons to Camp Schurman

- Friday. Skied across the Carbon and Russell glaciers to Observation Point

- Saturday. Down-climbed Ptarmigan Ridge then skied the Puyallup

- Sunday. Icy ski up Puyallup, rappelled to the S. Tahoma, camped on Van Trumps

- Monday. High-tailed it down the Wilson and to the parking lot

We are hardly the first to conceive skiing around Washington’s Mount Rainier. It was first encircled at timberline over 100 years ago when a three-week expedition helped survey the Wonderland Trail in 1915. Dee Molenaar helped evangelize the idea of a high glacier route in a trip report published in his 1971 book, The Challenge of Rainier. But in spite of its rich history, only a handful of mountain enthusiasts have completed the route—dubbed the “High Orbit”—and the line remains largely unknown.

The winters of 2013-2014 were banner snow years with the highest recorded snow accumulation of the past 50 years. Hundreds of feet of snow loaded the glaciers, causing them to accelerate down the mountain. The glacial rush-hour caused new pileups of crevasses, sometimes forging entire new routes. On top of this, dubbed the “ridiculously resilient ridge,” 2015 was an exceptionally dry year in the Pacific Northwest. While we could look forward to an unusually long weather window, only shallow winter snow bridged virgin crevasses on the route.

Diving headfirst into the shallow end, we immediately cross the Emmons glacier from Little Tahoma, the largest glacier in the lower 48 and the first in a string of 17 such glaciers on our trip. Like reading iced tealeaves, the Emmons could foreshadow our success or seal our failure.

And progress is pathetic. Tied together by 30’ of cord, we cautiously eke down the Emmons through a labyrinth of icefall and seracs. Chris bends a pole early in the morning while trying to control his descent.

“Huh…” he mutters. Chris curiously considers his pole’s new shape. We are going exceptionally light, carrying half a rope, a small tent and…heck, we are even sharing a sleeping bag. It becomes crystal clear that we need everything in our small packs to succeed. Chris’ bent pole is like a snowball across the bow that our fast and light, hold-no-bars (or back-up) plan could cartwheel into disaster pretty quick.

Crawling four miles in ten hours, we finally crest Camp Schurman at 9400’ as dusk falls on Rainier’s Emmons-Winthrop route. Fed and exhausted—we flop into our bivy tent to rest.

Cue the full body cramps. Chris, having skimped on fluids, fights back waves of surging muscle spasms rolling through his body in 30-minute intervals. In the dark, between Chris’ outbursts, I admit I might be getting too old for this.

“We need a solid day’s progress, way better than what we did across the Emmons.” I try to restack my confidence. Chris’ cramps fade and we finally drift to sleep.

Experience pays dividends, and in the morning we swiftly chomp through the miles under the imposing north face—which is good because I promised Chris this would be a walk in the park (albeit Rainier National Park).

Along the way I glance up at Liberty Ridge, a prominent line that cuts the formidable Willis Wall. It’s a route I climbed back in 1999. The ridge is known to be the only “safe” line that punctuates Rainier’s nordwand. Yet just last June six climbers washed off the route.

“Liberty looks trashed,” Chris points at its upper route. Fresh avalanche debris plasters the smooth high slopes. “It may be a while before Liberty returns to good nick.”

Lenticular clouds threaten to pull the hood over the summit all afternoon and continue to stir ominously in the North Mowich chasm. Chris and I spend the evening trying to piece together the puzzle that completes the descent off Ptarmigan Ridge, but it’s impossible to solve with the cycling weather.

“We’ll see what tomorrow looks like,” Chris shouts over the wind.

We crawl in our tent and put it to bed—or at least we try to as bursts of wind charge the tent like a bull throughout the night. But in the morning we wake up with a rested perspective, clear skies, and an eye on a 1500’ talus slope plastered in Styrofoam snow all the way to the North Mowich floor.

After traversing a knife-blade ridge, we unclip from the rope, strap skis to the packs, and feel our nerves tighten as we each pick our own line down the relentless grade. Like two flecks of pepper on a table of salt, I feel insignificant and exposed on the massive slope. Two hours later we finally roll out into the basin and scamper to a safe place where we can strap back into the comfort of our skis.

On the scale of big, Rainier is massive. It’s unlike anything else in the lower 48. We constantly are readjusting time and perspective to swallow its supersized portions. Yet as we ski off the Mowich and into the Edmunds, the ratio spontaneously shrinks. What appears far is confusingly close. But the terrain doesn’t give up without a fight. Our path ping-pongs across the glacier, in and out of shadows, across slush and bulletproof ice until it finally eases out onto the Puyallup plateau below the Sunset Amphitheater.

We probe a safe-zone for hidden holes and then set up the tent under a turquoise-blue canvas where we watch Seattle’s evening skyline ignite below.

After four days moving as one, Chris and I become more intimate with the terrain and conditions. Already behind schedule by a day, we long to close the gap in one final push. To make it work, though, we’ll have to push the hands on the mountain’s face from 9 o’clock to 6 o’clock—a quarter of the route. But if we’ve learned anything, it’s that the mountain sits in its own time zone—impervious to the wants or demands of our civilized schedules.

We break camp at first light and ski up a dire 2000’ slope that chokes into a narrow ice chute at Puyallup Pass. While Chris is using ski crampons that bite the ice under his bases, I resort to weighting my ski’s metal edges for traction. I jam my pole under my downhill ski to keep my edge from slipping out.

In reality, if one of us slips it’s going to be a long slide to the bottom of the slope in a rat nest of rope, sharps, and edges… or worse yet, we pitch off the cleaver entirely.

“This is getting old!” I shout to Chris, the most cranky I’ve been the entire trip. “We gotta get off this steep ice.”

We shimmy over to a snow shoulder below St. Andrew’s Rock to set up a grim belay in a crap chute filled with fresh debris that sloughed from above. I jam my ice axe into the snow and clip into it for safety. Chris turns around and I pull his axe out… with it I watch his helmet drop off his pack and accelerate down the wall. We both watch it disappear and without a word exchange skis for crampons and descend into the slidezone.

The Tahoma glacier rounds into the South Tahoma glacier, which relaxes into the Pyramid and into the Kautz, and finally yielding into the marshmallowy Van Trump glaciers. We are within striking distance of the truck, but late in the day seems to foster poor decisions. Rather than push our luck, we set up one last camp and decompress on the week’s events.

Though we are finally safe, the mountain doesn’t loosen its grasp on us. The horror show of the Emmons, Mowich, and Puyallup replay in my dreams. To save weight, we’ve shared one sleeping bag that Chris pins shut with his arm to keep the heat from chimneying out between us. As I roll over, I pull the bag out of Chris’ hands, which works into his dream as losing his grip on the line to me. Chris wakes in shivers, and then twitches back to sleep.

Dee Molenaar penned the High Orbit near the end of his book. But it’s not an afterthought. Rather, it’s a graduate school chapter for those ready for a larger commitment.

The orbit was a culmination of a lifetime of experience, drawing from all of our climbs, travels on glaciers, and endurance pursuits. As we drop to the Paradise parking lot, Chris and I agree it was likely the trip of our lifetime. A walk in the park, just like I promised.